How About Handling Children With Kid Gloves?

I haven’t encountered the word ‘discipline’ so often anywhere else in the world as much as I do in newspaper reports in India. Take last week, for example. Discipline in one school suffered a big blow because a Sikh boy defied rules and cut his hair. Some 10-year olds in another school pulled off a noxious prank by urinating in class – an act of indiscipline that had to be dealt with by expulsion from the institution.

Adults in New Delhi did not fare any better. A Shiv Sena MP raised a storm when he dared to stand up in Parliament and question the role of the PMO’s office in the UTI financial scandal. Indiscipline within the ranks? The Prime Minister sulked, then threatened to resign, and finally the NDA went into a huddle to draw up new rules for enforcing ‘party discipline.’

In other reports, laments for the lack of discipline on our roads, in our civic life and in government offices made a frequent appearance. And in the middle of all this, I wondered as to what we meant by and wanted from discipline in the first place? Isn’t it surprising that in a chaotic democracy such as ours, we’re so obsessed with the use and enforcement of this archaic military-style word with all its overtones of crime and punishment?

My Random House copy of Webster’s College Dictionary lists about 11 meanings for the word ‘discipline.’ Most of them are variations on the theme of “to bring to a state of order and obedience by training and control.” I see the necessity for order but wonder if the emphasis on bringing order through obedience and control is appropriate for the schools and government and polity of a society that is, or is trying to be, educated and democratic….

Let me elaborate. If the intent of education today (and most private schools say it in as many words in their fancy brochures) is to inculcate a sense of responsibility, encourage the process of independent thinking, and help individuals develop their own unique sets of talents, then the traditional definition of discipline has no place in a school/college. Individuality does not flourish under obedience and control and responsibility cannot be taught to those who are used to having order imposed by a superior. I wonder if our institutions face a problem with order in their schools because they’re trying to combine some modern educational methods with old-style Indian ones…

Western education concentrates, from the very early years, on teaching responsibility and independence rather than reading and writing. My son’s preschool class in the US was full of precocious three and four-year-olds who served themselves (complete with spills and messes) at the luncheon table, used cutlery (however ineptly) to eat their own food, buttoned their jackets, took turns feeding the class pets, and switching off lights when leaving the classroom. If the children forgot or hesitated to do what was expected of them, gentle reminders were issued, subtle hints given, and techniques demonstrated again and again until they became second nature to the kids. By the time these preschoolers reached kindergarten, they knew what was expected of them in the larger public setting of a big school – how to wait for their turn when sharing play equipment, how not to interrupt others when they are speaking, how to leave quietly to go to the bathroom or the water cooler to attend to their own needs rather than interrupting the teacher in the middle of a lesson, and how to use classroom materials in a manner that was not destructive. Personal mannerisms, appearance, and opinions were considered a matter of individual and creative expression and not subject to any rules. The school’s list of don’ts and not-alloweds was kept to a minimum, in the belief that these should be applied only in situations that have the potential for causing discomfort or harm to others. My son’s best friend in kindergarten appeared for several days in class wearing his clothes inside-out – just because he wanted to experiment with a new look! His teacher did not turn a hair, leave alone admonish him.

In the traditional Indian gurukul system of teaching, students subordinated themselves to their teacher or guru. Instructions were carried out unquestioningly and criticism was never levelled directly. The guru was learned and wise and his job was to teach while the students attended to his other needs.

Even today, in India, arguing or showing dissent with elders is considered disrespectful. On the other hand, parents attend to every need of their young and sometimes not-so-young children by feeding them with their own hands, dressing them, bathing them, and not asking them to share in tasks around the house because this is the manner in which we express love for our children. We spend time teaching them alphabets and numbers at a young age because these, to us, signify education.

I am not passing a value judgement on either of the two systems. I’m suggesting that our expectations from today’s education are at variance with our traditions and that is why we have ‘problems with discipline.’ Our teachers find it confusing to alternately act friendly and strict, to ask for free expression of feelings and then control the ensuing pandemonium, to desire a respectful ‘good morning’ but also allow for a child’s ‘bad mood.’

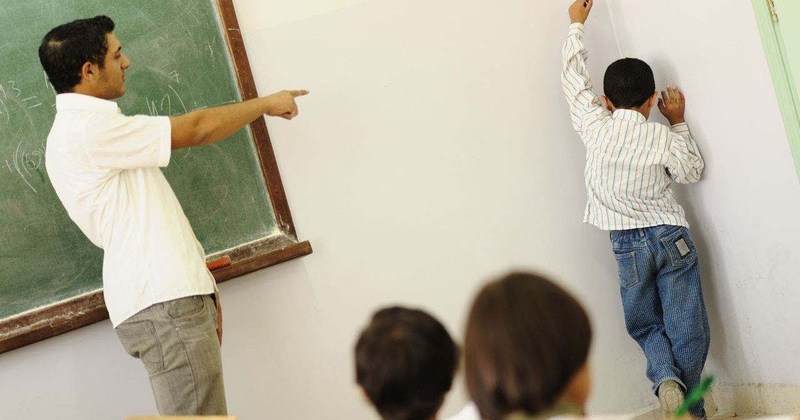

But unless these issues are addressed by schools and sorted out by educationists, they will eventually be more hard for the children that we are raising because we’ll continue to send them mixed messages. In today’s classrooms kids are encouraged to be curious with academic material but not in questioning the logic of elders who ask them to walk in a straight line or sit with fingers on their lips. They are not given the latitude to dress their individual bodies and hair in the manner they please but are expected to come up with creative solutions and original answers to problems in class. They are bombarded with school mottos enjoining morality, integrity, and virtue but are not taught, within the ripe social setting of the school, skills necessary to solve interpersonal problems, deal with conflict, and use facilities and materials in a responsible manner. And so we continue, when faced with a problem, to resort to good old discipline ? the kind that believes in corporal punishment, penalties, expulsions, silences, a good scolding, public humiliation. It toughens us, teaches us to be defiant and rebellious, to lie with a straight face, and to come up with creative excuses to escape punishment. But order it does not bring and responsibility it does not teach.

(This article was first published in my weekly column The Way We Are, in Chandigarh Times, Times of India, on August 14, 2001.)