The General and the Ladies

In the far northern end of Ladakh, in the rocky wilderness of a narrow, boulder-strewn valley flanked by lofty blue-black tors, lives a populace of some 2,600-odd Balti-speaking Muslims who are followers of the Ahle Hadees and Noorbakhshi sects. Their villages, starting with the little hamlet of Bugthang and ending with Thang which is perched high on a muddy cliff above the river, follow the course of the river Shyok (the river of death), before it disappears over the Line of Control (LoC) into Pakistan. The five villages — the others are Turtuk, Thyakshi and Chalunka — were themselves part of Pakistan, until the Indo-Pak war of 1971, when India gained and retained control over them.

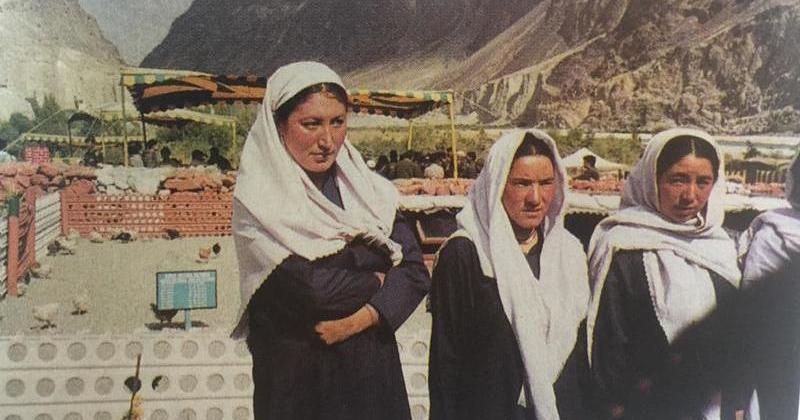

History is typically not fair to those whose lives skirt man-made borders. But in this remote and almost inaccessible corner of the planet, it has dealt more blows than usual to the lot of the women whose cream-and-roses beauty would turn ramp models green with envy. Several of them are the wives and daughters of men who were soldiers in the Pakistani army — men who died, or were afraid to return to homes that are now in India, or simply preferred to stay on and work for an army they were loyal to.

War Against Women

Rahima Begum, her face touched only fleetingly with the burden of her 50-plus years, had one such husband whom she has not seen since the early period of their marriage. She knows however, that he has found another bride across the LoC, fathered children other than the two daughters she has from him, and lives in a Pakistani village that is downstream from the same waters that irrigate her fields in India. Rahima herself did not marry again for a long time, not until she had finished educating her girls.

Other women, like the hapless Safora Begum and Najumo Begum, had their family lives disrupted when their spouses were arrested on charges of aiding and abetting Pakistani spies in the famous Turtuk arms case of 1999. And several more spend a good part of the year alone as the local men leave to hold down jobs as porters and temporary labourers in other parts of the state. Single-handedly, they cultivate the meagre fields and keep the home fires burning through the long hard winters when temperatures dip to below 20 Celsius. Heads covered with ‘chaddars’, they nurse and carry young children on their backs as they go about the daily summer business of feeding scrawny livestock and spreading vegetables out to dry in the sun.

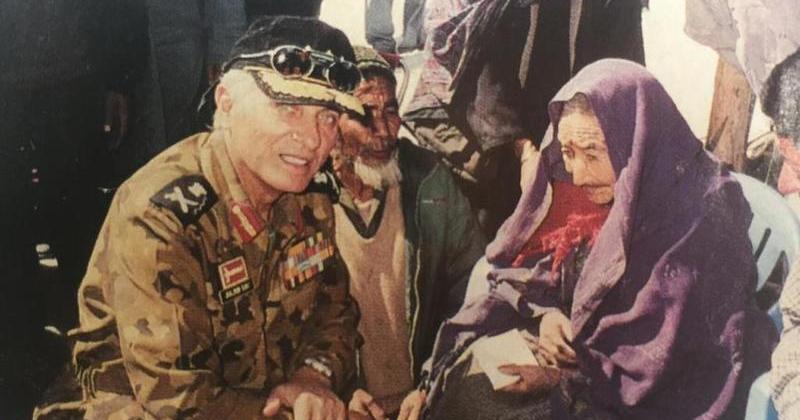

It is no wonder then that Lt Gen Arjun Ray, General Officer Commanding (GOC), of the Indian Army’s Leh-based 14 Corps, feels that empowering women is the key to fighting the growing sense of alienation in this part of Jammu & Kashmir.

Army Initiative

“Women are more concerned with home and security, the education of their children, and the work opportunities this will bring them,” he says, and adds, “an educated mother benefits her own family and society at large.” Others in Ladakh, like Harvard-returned professor Siddiq Wahid, echo this feeling: “Do you see educated women wanting their children to grow into terrorists?”

The architect of Operation Sadbhavna, a programme that has the army building and running schools, hospitals, vocational training centres, and income-generating projects in some of the most remote border villages, Lt Gen Ray is not satisfied with the description of his efforts as ‘scaled-up civic action’. He demands nothing less than complete involvement on the part of his officers and men with the locals. “I want you to think of yourselves as citizens first and soldiers second,” he says to them during one of the innumerable ‘sensitising’ workshops and training sessions.

In Turtuk, next to the whistling Shyok river, I meet two enthusiastic women army officers, Dr Nima and Dr Arpreeta, who staff the local Ayesha Sidhika Hospital. “Last night, there were complication with a Caesarean delivery that I was handling,” recounts Dr Nima, “so we drove in the ambulance to the army hospital at Hunder (four to five hours away) where the baby was delivered safely.” Dr Arpreeta, a dentist, adds, “I don’t think of my job as being just to hand them their medicine. The girls from the vocational centre tell me their problems. I feel good about what I’m doing here at the end of the day.” The doctors also train the young women of the region in nursing and lab work, they visit the vocational centres to talk to children and teenagers about health and hygiene, and help airlift those in need of urgent medical attention to army hospitals countrywide.

Caring in Kargil

I leave Nubra Valley and head towards Kargil, Dras, and to Mashko Valley beyond — most, if not all of which formed the battlefield of the two-month war fought with Pakistan in the summer of 1999. The first view of Kargil city, approaching from Leh, is quite spectacular — a beautifully rounded valley that is wide enough to hold the shimmering confluence of the Suru, Wakha and Dras rivers, broad terraced steps shouldering the weight of houses and streets, and distant dark peaks to the left and beyond. On getting closer, I see the bombed-out ammunition yard, the crush of army vehicles ferrying supplies, and a field stacked high with gas cylinders awaiting delivery. Kargil is as unlikely a setting for the cruelty of war as the French Alps must have been in 1940.

But even more unlikely is the sight of city-bred volunteers from as far afield in India as Baroda and Bangalore. Here to help teach in schools, rehabilitate the challenged, and even train dogs, are young men and women who are staying as guests of the Indian Army and earning nothing more than a tiny stipend by way of expenses. And although the civilian-army interaction is “difficult” at times, according to Kaneez Sait, a Masters in Psychology from Bangalore who teaches at the Army Goodwill School in Kargil, “the experience has been worth it for the children that I taught and some of the people that I met”

Lt. Gen Ray has actively sought to network NGOs and private individuals into what he terms the process of “nation building”. That his experiment is paying off to some extent is apparent from the clamour for more “city teachers” that greets me in the yard of the army-run Dras Public School. Jaya, a young woman from Coimbatore, has barely spent a couple of months teaching here, but Sheharbano and Asadullah, local teachers, are convinced that they want more volunteers like her rather than just the people from the Army Education Corp they have been sent in the past. “We learn new ways of functioning from Jaya madam,” they say.

At the Vocational Training Centre in Moradbag in Mashko Valley, the young Muslim women who come to learn knitting and weaving and computer skills, are enamoured with Rohini, a young psychology major from New Delhi, who sometimes tutors them for the Open School exam, speaks on issues related to hygiene and cleanliness, and also works with challenged children at the Army’s Umeed Resource Centre in Dras. Satisfied with the work she is doing, she is critical however of the army’s accepting volunteers regardless of “whether they are capable of doing the job or not”. Lt Gen Ray, on the other hand, says he will work with anyone who wants to help the army in its efforts to “curb militancy through goodwill”. A fresh wave of 25 volunteers from Bangalore-based NGO Prakruthi is now getting ready to come to Ladakh. At other times, gynaecologists and sculptors have arrived at short notice at the doorsteps of the 14 Corps, as have mechanical engineers and software experts. They are placed in field stations as far apart as Batalak and Turtuk, where they work alongside other officers and men, to help people who may never have seen any other faces from any other part of India apart from those of Indian Army personnel.

The fact that their presence is having an impact on impressionable minds is apparent from how adolescent girls like 17-year-old Ameena Bano and her friends view their future. Gathered around a bus waiting to transport them to after-school vocational training activities (usually involving stitching and sewing and cooking) in Partapur, they giggle and say nothing at first when asked if they want to get married soon. Then, as the bus pulls away, a couple of them lean out to shout to me: “Not until we’re 30, we’ll work first.” Their confident laughter rings out to the surprise of bored-looking men smoking ‘beedis’ on bazaar stoops.

(This article first appeared in Femina magazine, February 15, 2002)