Chutney Music: A Vibrant Mix of Bhojpuri Beats and Caribbean Calypso

What happens when the dholak and dhantal from the heartland of India meet tassa drums and Soca beats on the shores of the Caribbean? A delectable fusion called Chutney music, of course!

In 1970, a young singer named Sundar Popo from Trinidad, catapulted to fame in the small Indian community of the Caribbean with a song called Nana and Nani. The droll and witty lyrics, a mix of Hindi and Trinidadian Creole, dwelt on the comical everyday affairs of a grandmother and grandfather living in a small town. Backed with the music of the dholak and dhantal (as well as the guitar and synthesizer), the song instantly became a chartbuster, giving birth to a new form of music known as ‘Chutney’.

It was hard to find anyone not humming the lyrics of this hugely popular single – the strains of ‘Nana drinkin white rum and Nani drinkin wine’ were heard just about everywhere, from the dance halls of Anna Regina in Guyana to the rum shanties of Belle Garden in Tobago.

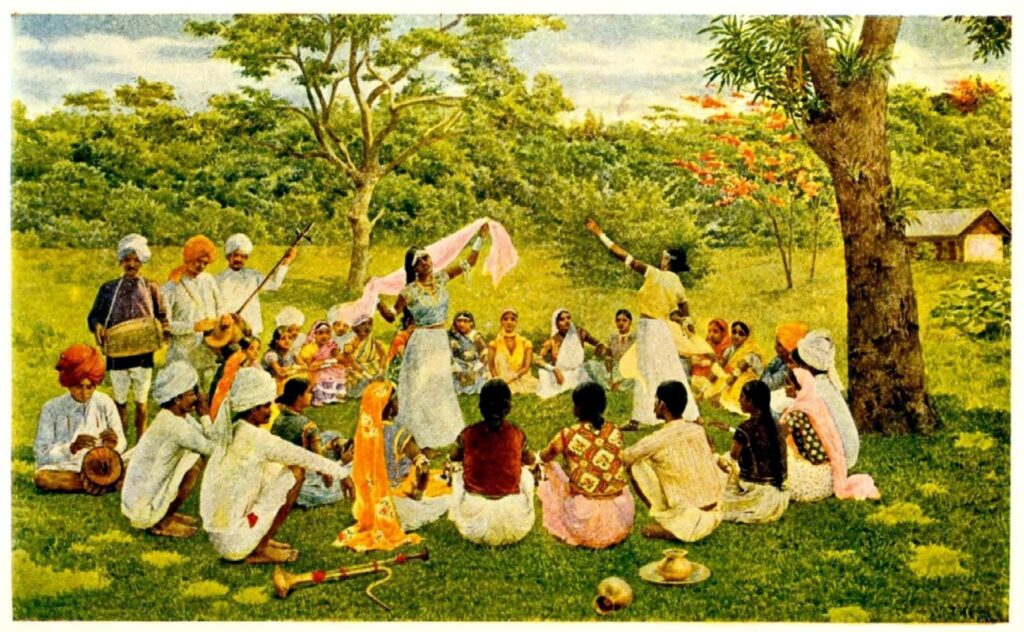

Indian music first came to the Caribbean with East Indian indentured labourers, who were brought by the British to work on the sugar and coffee plantations of the colonised islands. Most of them were natives of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Bengal. Many of them settled in Guyana, Trinidad and Jamaica after the British left. Others, brought by the Dutch, stayed on in Suriname.

Isolation from not only the homeland but also from other West Indian communities among whom they settled helped the Indians retain much of their ancestral culture. An important part of this was music – mostly bhajans and devotional songs sung in Bhojpuri Hindi, which included the use of traditional Indian instruments such as the harmonium, sitar, tabla, dholak and dhantal. But slowly, as the community grew and began to imbibe influences from its surroundings, Calypsonian rhythms and the fast and stirring beat of tassa drums began to make an appearance in Indian homes.

The songs were still mostly in Hindi, sung with a distinctive West Indian Creole accent. The lyrics centred around relationships and the mundane happenings of daily Indo-Caribbean life, but sometimes echoed the frustrations engendered by political subjugation and colonisation.

But it was not until the emergence of Sundar Popo and his fusion music that Chutney was truly born. However, with hardly any other new talent in the field, Chutney soon began to fade out of the limelight in which it had so suddenly appeared. For a while, it looked like this interesting genre would be lost to history. At the same time, Caribbean music too was evolving, moving from traditional Calypso to a new blend with American Rhythm and Blues that came to be known as Soca. No one knew then that Chutney would put in another appearance on the music scene, in an avatar called Indian Soca.

This new style of music incorporated the more Calypso flavour of the steel pan, synthesizer and electric guitar. The lyrics changed. They were dominated less by Hindi words now and mostly sung in West Indian Creole. The biggest change, however, was that Afro-West Indian singers picked up the new fusion and became the dominant proponents of Indian Soca in its early days.

Most East Indians did not embrace this new form. Many looked askance at this threat to their traditional culture, rejecting hits like a song called Raja Rani: ‘Oh Rani, I want to marry Hindustani, I love curry, so beti (girl), gimme plenty’. Or, Marajin, a song where an Afro-West Indian singer, Sparrow, declares his love for an East Indian woman, ‘Marajin, Marajin, oh my sweet dulahin (wife)’.

Sparrow’s Marajin caused such a huge outcry among the Indians of Guyana that the song had to, eventually, be banned.

It is interesting that while the Afro-West Indians sang about their love and admiration for beautiful East Indian women, the male East Indian singers did the exact opposite. In Give Me Paisa, singer Kanchan decried all East Indian women as gold-digging housewives who only want ‘jewellery, sari, necklace and t’ing, so just give me paisa (money)’. In ‘Darlin I Go Leave You’, Anand Yankarran too expressed scorn for East Indian women – calling them ‘cheats’ and lazy.

But something more exciting was soon going to happen to Indian Soca, the entry of an East Indian woman on the Chutney scene.

Drupatee Ramgoonai, from Penal in the deep south of Trinidad, burst onto the music stage in 1987 with the release of the single ‘Pepper Pepper’.

The lyrics of the song have her seeking revenge on a husband disinterested in their marriage. Her solution? Put pepper in his food and hear him cry out: ‘Pepper, I want Paani (water) to cool meh, Pepper, I want plenty Paani’.

Even as Pepper Pepper moved up the Soca charts, conservative Indians went on a verbal rampage against Ramgoonai. While it was considered acceptable for East Indian men to poke fun at “their” women, an Indian woman who dared to sing Calypso was said to be bringing disgrace to the community.

Mahabir Maharaj, writing in the local community newspaper Sandesh, echoed these sentiments: “…for an Indian girl to throw her high upbringing and culture to mix with vulgar music, sex and alcohol in carnival tents tells me that something is radically wrong with her psyche. Drupatee Ramgoonai has chosen to worship the gods of sex, wine and easy money.”

But the highly talented Ramgoonai was unstoppable. She released another album a year later. Her new hit titled Mr Bissessar was all about her adoration for a Trinidadian tassa player named Bissessar. This song, which would later come to be known as Roll Up De Tassa, sprang to the No. 1 spot within two weeks of its release in 1988, in every country in the English-speaking Caribbean. Within no time, it had successfully crossed over from the islands and found a place on the Soca charts in the US, Canada, and England. Ramgoonai had made history. She was not just the first East Indian woman, but the first East Indian Soca singer to have a No. 1 hit.

It was time for Popo to pass on the Chutney mantle to the reigning queen of Indian Soca – Drupatee Ramgoonai.

Among the later stars on the Chutney scene, Terry Gajraj deserves to be remembered for his album of Guyanese folk songs, entitled Guyana Baboo. As younger Indo-Caribbeans from the islands began to emigrate to the US and Canada on the North American mainland, the meaning of ‘homeland’ for them changed – it was no longer India but the small towns of Trinidad and Guyana where they left friends and family behind. In Bangalay Baboo, Gajraj evoked memories of Guyana for them by singing, ‘I come from the land, they call Guyana, land of de bauxite, de rice and sugar’. Terry’s songs played in the homes of virtually all Indo-Caribbean communities in the US and Canada, nostalgic for their roots not in India but the wedding houses and temples of Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad.

Chutney had now truly become an international genre, moving out of the Caribbean and onto the world stage.

Indian Soca may not be sampled much in India as yet but its popularity in the US and Canada continues to grow, thanks to the number of Indo-Caribbeans settled in New York and Toronto. These immigrants have their own record companies – Jamaican Me Crazy (JMC) Records, Spice Island Records, Mohabir Records, etc. Nightclubs such as Soca Paradise and Calypso City in New York, and Connections and Calypso Hut in Toronto, are the new hangouts, instead of the wedding halls and rum bars of the Caribbean.

The fact that most of these younger East Indians don’t even understand Hindi makes their love of this music all the more intriguing. But Chutney is, perhaps, more than just music for them. History and geography may have removed them from their roots in India but the music is a reminder that they are not drifters, that their pasts are firmly anchored in an ancient tradition even as their future has taken them to the New World.

(This article appeared in The Better India on July 5, 2016.)