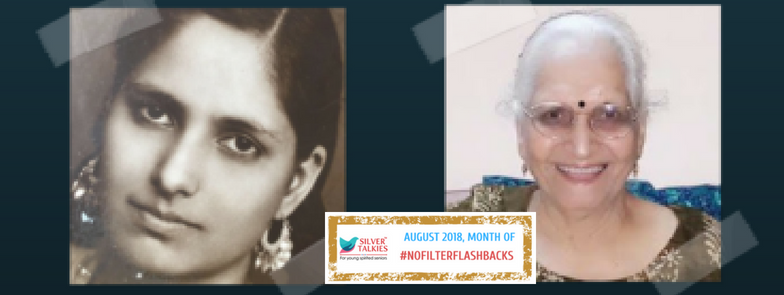

My Mother’s Memories: Growing Up Among the Pathans of Peshawar

A childhood spent playing gulli danda with her brothers, wearing a burkha to school, sleepwalking at night, making her own ice cream, and snacking on dry fruits from Kabul…my mother’s memories of her childhood.

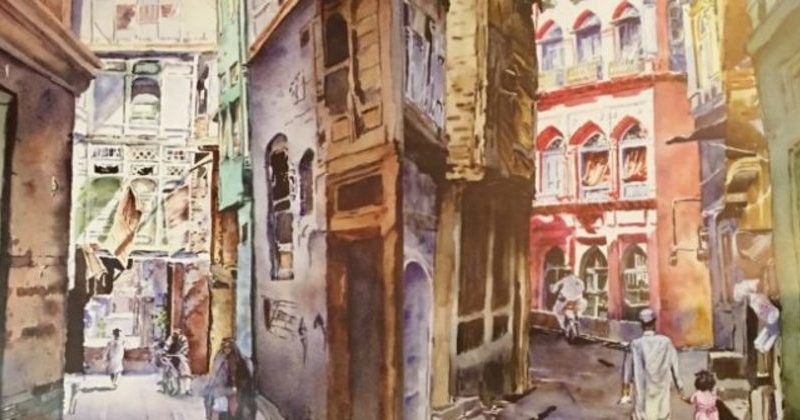

My mother, Vimla, was born in a small town called Hoti, in the remote Mardan district of Peshawar, close to what is now the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan but was then undivided India. Wikipedia tells me Hoti is a union council in the Mardan District of Pakhtunwala. The town is located at an altitude of 284 metres and lies just west of Peshawar, the capital of the province, and is inhabited by the Kamalzai Pashtuns, a sub tribe of Mandanr Yousafzi. The people of this area only speak Pukhto, and adhere strongly to the Pukhtoon traditions of hospitality and loyalty.

My mother was 10 years old when the British left, the Partition took place and India and Pakistan became two independent countries. Her family, both parents and 7 young children, were vacationing in Haridwar on the Indian side when the mayhem and violence of the Partition started. They were stranded, unable to go back home to Hoti, with just the clothes on their backs. But, as a result, all of them survived and did not face any of the violence that befell their neighbours and loved ones trying to cross the border. My grandfather went back across the border to help his younger brother and his family escape as well and they all took refuge in Agra. Later, the two started a business in the shoe and leather market there, which went on to become a success.

My mother, now almost 83, recounts her faint childhood memories of growing up in Peshawar in snapshot conversations. Here are some of them:

“My father (Papa ji), a tall strapping proper Peshawari Pathan, was a cloth merchant in Hoti and I lived in a huge house there, along with my mother (Jhai ji), paternal grandfather (Lalaji), four brothers and two sisters. The front of the house was where Papaji kept his goods, then you had to cross a huge courtyard with a well at the back before getting to the verandahs, living rooms and bedrooms.

I used to go to school every morning. The school would send a woman called Mai to knock on each door and collect the kids who had to go to school. She would go around twice and knock on doors – the first time to let everyone know she had arrived and then to actually pick up the 10-15 girls in her charge. Once I reached Class 3 I was old enough to go to school in a proper ghoda gadi (horse driven carriage) because that’s how girls from good homes travelled.

Since the residents of the area were predominantly Muslim Pathans, their wives and daughters covered themselves from head to toe in burkhas. I was fascinated by this outfit and begged my father to get me one, despite the fact that we were Hindus. My father did not bat an eyelid and had a burkha stitched for me the very next day. I wore it proudly for a long time.

Temperatures were extreme in Hoti. The summers used to be blazing hot and the winters extremely cold. In summer, I remember a pankhawala sitting and fanning the occupants of the living room – usually my father and grandfather. I used to escape to that room often when my mother scolded me, knowing that she would not show her presence in the room where Lalaji was sitting.

In winter, my siblings and I used to make our own ice cream. All we had to do was mix milk and sugar, pour it into a shallow container and leave it overnight on the terrace. It used to be frozen by the morning!

We used to keep socks and sweaters next to us as we went to bed and used to wear them and rush to the kitchen first thing in the morning. It used to be warm there with a wood fire burning. We had two kitchens – an open one for summer and the enclosed one, where they burned wood and cowpats, for winter. We used to eat tandoori rotis in summer so there was a clay tandoor in the summer kitchen.

I used to sleepwalk as a kid. This was of major concern to my parents because of the well in the courtyard of the house. A family conference was called and it was decided that the well be covered for good lest I fall into it some night. So that is what they did.

I remember eating abundant amounts of dry fruits as a kid. Badam (almonds), pista (pistachios) and chilgoza (pine nuts) used to come from Kabul, which was not far off. It used to cost hardly anything to fill my pockets with the pine nuts and go skipping off to play. One rupee had 16 annas, 1 anna had 4 paisa, 1 paisa had 2-3 dhelas, 1 dhela had 3 pai/damdi (I think)!

After our nap in the afternoon, we used to buy snacks from the hawker who came around with two tokris (baskets) balanced on the edge of a bamboo pole to the house. He used to bring freshly roasted channa, corn and peanuts. We had our pockets forever full of snacks!

I used to play gulli danda with my brothers because my sisters were too young for me to play with. Or I would play stapoo with some of the girls in the neighbourhood.

My mother used to speak to all the servants in Pushto but we spoke Punjabi at home. One day Jhai ji asked me to go pick up a pot of boiled chhole from the shop at the corner. For some reason nothing was being cooked at home that day. They usually did not send me out to get anything because I am a girl but that day my mother sent me. And I bought half a kilo of boiled chhole for only one dhela.

I had to wrap a chunni (scarf) around my head before going out despite the fact that I was so young. In fact Jhaiji had to wear a double chunni – one of mulmul and one of a thicker cloth – every time she went out. The women usually did not show their faces to the elderly men of the community. When Lalaji used to come home in the evening, he would stand at the corner of the lane to our house and cough discreetly. This was a signal to all the women who happened to be sitting outside and gossiping with their neighbours to go inside. The purdah system was very strongly followed there because of the many Muslims I guess, although people did not differentiate between the communities at all. I grew up never knowing the difference between Hindus and Muslims.”

(This article appeared in Silver Talkies on August 6, 2018.)